Reviving Telangana’s broken revenue system

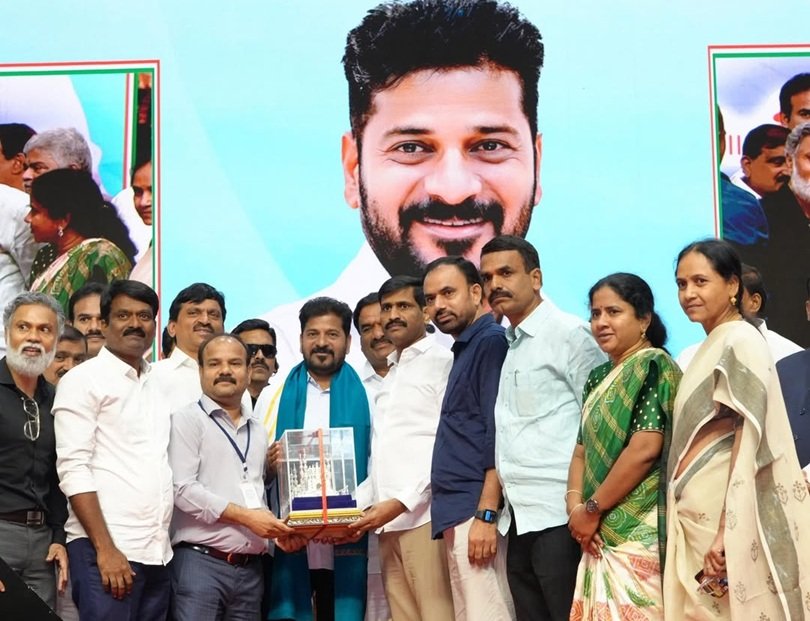

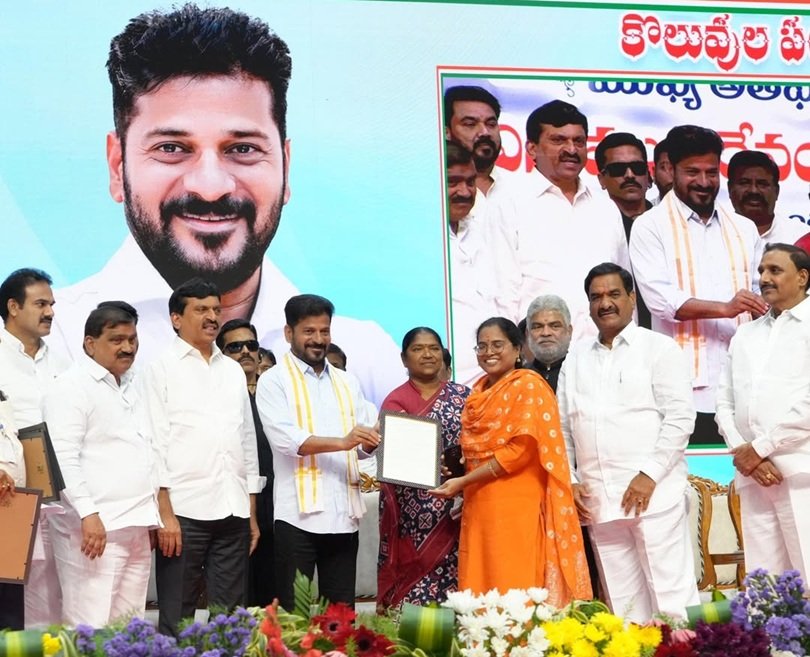

During the ‘Koluvula Panduga’ programme, when Chief Minister A. Revanth Reddy handed over appointment letters to over 5,000 newly recruited Gram Panchayat Officers (GPOs) last week, it was, in many ways, an attempt to breathe life back into Telangana’s grassroots revenue system that had been dismantled, discredited, and dismissed during the Bharat Rashtra Samithi (BRS) era.

With these job offers, Revanth Reddy emphasised that the Congress government had fulfilled its poll promise by “dumping the flawed Dharani portal in the Bay of Bengal” and introducing the Bhu Bharati Act to resolve land disputes transparently, urging the officers to act as a bridge between the government and the citizens while restoring public trust.

Unsparing in his criticism of his predecessors, the Chief Minister accused the BRS government of scrapping the Village Revenue Officer (VRO) and Village Revenue Assistant (VRA) system only to facilitate large-scale land grabs through the now notorious Dharani portal. By painting grassroots revenue staff as “dacoits and thieves”, the BRS effectively removed the only officials who had detailed, village-level knowledge of land records – knowledge that could have obstructed encroachment.

But Reddy’s sharpest question cut through the noise: “Will the government scrap the entire system if a few are found guilty of wrongdoing? Do we burn the house because there are rats?” It was a rhetorical swipe not just at the past regime’s policies, but at the very logic of dismantling a system completely for selfish gains.

Dharani: A flawed portal

For ordinary citizens, the flawed portal Dharani was a source of anguish. Revanth Reddy recalled chilling episodes: a farmer setting an officer on fire in Ibrahimpatnam out of frustration, women throwing their mangalsutras at officials in Sircilla, and countless landowners stuck in limbo. These were not outbursts against individual officers, Revanth argued, but against a “virus” that infected the system.

The Congress, true to its campaign promise, wasted no time in “throwing Dharani into the Bay of Bengal”. In its place, the government introduced the Bhu Bharati Act, aimed at resolving long-pending disputes, especially those related to ‘sada bainamas’ (unregistered land transactions). The new law, he insists, is designed to be fair, transparent, and farmer-centric.

Rebuilding from the ground up

The revival of grassroots administration through the appointment of GPOs is central to the system before clicking the reset button. Unlike the faceless digital interface of Dharani, GPOs are expected to serve as a bridge between the government and citizens, especially the poor. They are tasked with implementing Bhu Bharathi in letter and spirit, addressing disputes swiftly, and restoring confidence in institutions.

The Chief Minister was blunt with the recruits: this is not just a job, but a matter of self-respect. The stigma attached to revenue staff during the BRS regime, he argued, can only be erased if the new officers work with integrity and prevent the Congress government from inheriting a bad name.

Land, legacy, and Telangana’s identity

Revanth Reddy cleverly tied present-day reforms to Telangana’s historical struggles. He invoked the sacrifices of Komaram Bheem, Chakali Ilamma, and Ravi Narayan Reddy, and the spirit of the Bhoodan movement. He reminded officers that land rights are not just an administrative issue but the very heart of Telangana’s political identity. “Land struggles defined our history. They will also define our future governance,” he said.

With this historical framing, and by linking the failures of Dharani to the betrayal of Telangana’s legacy, and showcasing Bhu Bharathi as a solution to make a return to that legacy possible, Revanth Reddy is making land reforms about not only correcting records, but also reclaiming identity.

Ensuring success at multiple levels

Nevertheless, the big question remains: will this revival succeed? Although critics point out that while scrapping Dharani addresses immediate grievances, building a robust, corruption-free revenue system is far harder, the Chief Minister is taking a positive step towards undoing years of damage by appointing GPOs and passing a new Act.

Transparency, however, will depend on political will, training, and whether officers resist falling into old patterns of patronage and corruption. Moreover, land disputes in Telangana are deeply layered – ranging from ownership battles to caste and community-linked claims. The success of Bhu Bharathi will be judged not by promises but by whether ordinary farmers actually experience quicker, fairer resolutions.

Still, by reviving the grassroots network and confronting BRS’s missteps head-on, Revanth Reddy has staked both political capital and moral ground. His government now has a chance to not only fix a broken system but also restore a measure of faith in the State itself.

If the GPOs deliver, this could be remembered as one of the defining reforms of Telangana’s second decade.

Gangadhar Mudhiraj

భూ భారతి వల్ల ఎటువంటి ప్రయోజనం లేదు..ఎందుకంటే ఇంతక ముందు ధరణిలో ఎటువంటి పనులు అయితే అయ్యయో ఇప్పుడు కూడా అవ్వే అవుతున్నాయ్ తప్ప కొత్తగా ఏం అవ్వడం లేదు.. ఒక్క అప్లికేషన్ approval కావాలి అంటే 6 నెలల సమయం పడుతుంది..తెలంగాణలో మొత్తం భూ సమస్యలు అనేటివి వుండద్దు అంటే గ్రామాల వారీగా సర్వే చేస్తూ వెంట వెంట ఆన్లైన్ లో అప్డేట్ చెయ్యాలి.. చాల మంది రైతులు కబ్జలో భూమి కలిగి వున్న వారికి ఎటువంటి పట్ట లేదు అలాంటి వలకి సర్వే చేసి వెంటనే పట్ట పాస్ బుక్ మంజూరు చెయ్యాలి.GPO వ్యవస్థని తీసి వెయ్యాలి వాలా వలన ప్రభుత్వానికి మరియు రైతులకు ఎటువంటి ఉపయోగ లేదు